Investors can’t afford to sit still and wait for companies to be mandated to disclose on social issues – although that is coming – warned Aviva Investors’ Richard Saldanha.

The global equity portfolio manager and lead manager on the Social Transition Global Equity fund said while we wait for mandatory disclosure requirements to be put in place, there is a range of options to gather information on how companies are managing their social footprint and, specifically, the key systemic risks related to social inequality.

Here, Saldanha answers ESG Clarity‘s questions on identifying social transition companies, aligning with the SDGs and red flags when researching human rights due diligence processes.

See also: – In the Hot Seat video interview with Richard Saldanha

First, can you explain the rationale behind the Social Transition Global Equity strategy? What are you looking for in the companies you invest in and what are you trying to achieve?

The Social Transition Global Equity strategy targets opportunities aligned to the principles of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals that support and benefit from the transition to a more socially equitable economy. We invest with an active, high-conviction approach to address the needs of investors seeking two objectives: delivering long-term capital growth and having a positive impact on the transition towards a more socially just and equitable economy.

First, we identify ‘transition’ companies that manage their social impact better than their peers and where we think we can engage to encourage them to go further. These companies play a profound role in shaping society by respecting human rights, providing decent work and acting as responsible corporate citizens – a framework previously set out by the World Benchmarking Alliance.

We also invest in ‘solution’ companies that provide specific groups or underserved communities with access to basic resources and services. These companies address areas where there are clear gaps in the public provision of products or services: access to education, access to healthcare and financial inclusion.

Can you explain how social inequality hinders economic growth and increases the probability of financial crises?

Inequality is not just a moral issue – it poses systemic risks that threaten economies and businesses. For example, OECD estimates suggest rising inequality reduced GDP growth by between six and nine percentage points in the US and UK between 1990 and 2010. One justification for higher inequality lowering growth is because it deprives the ability of lower-income households to stay healthy and accumulate physical and human capital. Because those on higher incomes tend to save more, and those on low incomes have less scope to invest in education and skills, inequality tends to sap overall productivity and impose a drag on growth.

There is also evidence suggesting that high levels of inequality can have a causal effect on crises. Indeed, there are reasons to believe that a prolonged period of higher income inequality in advanced economies played a role in causing the global financial crisis, by intensifying leverage and overextending credit against a backdrop of declining mortgage underwriting standards and increased financial deregulation.

How is the fund aligned with the UN SDGs?

The ‘S’ in ESG can fundamentally be drawn back to social inequality – in essence, the unequal distribution of human rights and resources. The United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights commits nations to recognise all humans as being born free and equal in dignity and rights regardless of nationality, place of residence, gender, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, language, or any other status. These human rights have been incorporated into international treaties, national constitutions and legal codes, and along with labour standards underpin 90% of the targets in the 17 UN SDGs.

That said, the fund’s holdings are aligned to seven of these UN SDGs – (1) no poverty, (3) good health and well-being, (4) quality education, (5) gender equality, (6) clean water and sanitation, (8) decent work and economic growth and (10) reduced inequality.

What do you look for when researching companies’ human rights due diligence processes? What are the red flags?

We look for companies to have a robust and multi-layered approach to conducting its human due diligence. The process should include setting out how monitoring is embedded as part of a wider risk management process, reporting salient issues and having an action plan agreed to address any issues identified on the way.

For example, US semiconductor firm NXP Semiconductors maps different risk levels of its supplier base for almost all of its procurement spend, discloses the number and types of violations that occur in its own operations and supply chain for each salient human rights issue and reports its remediation efforts. The company will continue to benefit from its more progressive approach to managing risks in its supply chain by meeting customer semiconductor demand, which we see contributing to more resilient margins through the cycle.

What about their responsibility to provide a safe working environment, products that do not cause harm and responsible tax behaviour? How do you analyse these?

Before we consider companies as candidates for the fund, we seek to exclude companies that cause ‘significant harm’. In addition to our firm-wide baseline exclusion policy (covering areas such as tobacco and controversial weapons) and exclusion criteria on climate and environmental harms relating to our broader Sustainable Outcomes franchise, the fund excludes companies that we consider to be causing significant harm to people – for example by applying global norms controversies and predatory lending thresholds. These negative impacts pose a risk to people and society and can also materialise as risks to the business.

For those companies within our investable universe, given the multitude of social responsibilities that companies have we tend to focus our analysis on those factors that are more material to each businesses model – for example US equipment rental company United Rentals we pay close attention to their efforts to efforts to monitor and report on health and safety performance, while for Bank Rakyat Indonesia we value the company’s relationship with Indonesia’s government, who have the power to support the company’s financial inclusion efforts or inflict significant penalties if it seeks to exploit these more vulnerable customers with products that cause harm.

The ‘S’ of ‘ESG’ has been notoriously difficult to measure. How do you approach this?

There are a few reasons why ‘social’ has been difficult to measure, one of which is that disclosures on social issues are poor. In the past companies have excused themselves from providing relevant social data by pointing to a lack of standardised reporting templates and frameworks, but soon, frameworks such as the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) will provide standardised metrics that all companies will have to report against and in the US, the SEC is currently considering mandatory disclosure on human capital topics. The EU and other countries are now also codifying the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights into regulation, requiring companies to disclosure their process for managing human rights risks.

In the meantime, investors can’t sit still and fortunately we have a range of options to gather information on how companies are managing their social footprint. Investors can begin by breaking social factors down into analysable dimensions, and various data sources are available to help provide initial inputs.

See also: – Investors ‘turn blind eye’ to social risks

It is important investors look beyond company reporting alone to gather these insights – NGO rankings, trade union analysis, civil society research all provide rich, counter narratives to what is found in the (often quite short) people section of a sustainability report. The most exciting part is bringing these insights together – drawing conclusions from qualitative information, engaging stakeholders and understanding the relationships between social and environmental outcomes. This can be painstaking work, but ultimately helps build a clearer picture of the opportunities and risks companies face

Where would you like to see more social disclosure? And regulation around this?

There is a tide of regulation emerging to mandate companies to either provide more information on the structure and treatment of workers, or to conduct a human rights due diligence to demonstrate they are managing their human rights risks and impacts effectively across the value chain.

On the workforce side, we are pleased to see considerable progress on human capital disclosures – a key indicator of momentum behind the social investing thematic. In June 2022 a group of academics sent a letter to the SEC outlining their views on what human capital disclosures could look like. The letter included three main proposals: management discussion & analysis, standardised disclosure for workforce investments, and income statement disaggregation.

Fast forward a year later to June this year, The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) released a proposal on the disaggregation of expenses on income statements asking for detailed information about the types of expenses (including employee compensation, depreciation, and amortization) in commonly presented financial metrics such as cost of sales, SG&A, and research and development.

A recent study by Professor Shivaram Rajgopal from Columbia Business School, highlighted only 15% of US public companies disclose their labour costs. Providing investors with this information makes it easier for us to understand a company’s cost structure, and more accurately calculate the leverage the company has to this cost base and the impact that it can have on returns on capital.

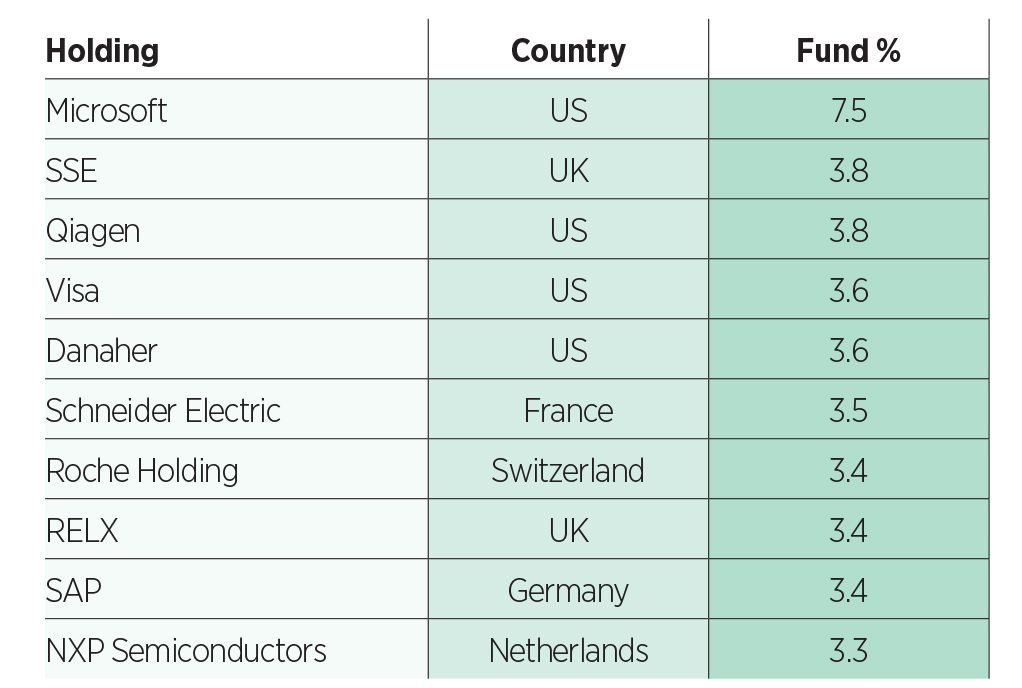

Top 10 holdings

Fact box:

- Launch date: 30 November 2021

- Fund AUM: $35.20m (as of 22 November 2023)

- Portfolio management team members:

- Richard Saldanha, portfolio manager

- Matt Kirby, portfolio manager

- Number of holdings: 36