Florida recently formally banned the use of social or responsible considerations in its public investments, and its Republican governor Ron DeSantis proposed anti-ESG legislation to make that permanent.

That happened the same day attorney generals from 21 states sent letters to proxy advisory firms ISS and Glass Lewis, accusing the firms of violating state laws, and asking them to elaborate on their advice to clients around ESG issues.

Those are among the latest indicators of a spreading anti-ESG movement in the US, one that many Republicans have started to use in a rallying cry against “wokeness”.

Numerous states have taken action to prevent public assets from including ESG considerations in their management, most commonly as a way to protect oil and gas interests. Texas, for example, has blacklisted 10 asset managers and nearly 350 funds that it has claimed boycott the fossil fuel industry. Recently, Florida moved $2bn in assets away from BlackRock, the firm that has taken the brunt of the attack on ESG across the country.

It had seemed like that anti-ESG trend ramped up to a peak last year – notably amid the US midterm elections. But if the early activity seen so far in 2023 offers any hint, it could be that things are just getting started.

“It has potential to have a big impact on who’s going to be [US] president,” said Ellen Holloman, partner in Cadwalader’s global litigation group. The anti-ESG issues “are going to play out in the next presidential election in the same say they did in the midterm cycle”.

Likely, there will be a lot of activity in the states where election results could be close, Holloman said.

The Sunshine State

Florida’s DeSantis, who is expected to declare candidacy for the 2024 US presidential election, “is leading the way for anti-ESG initiatives, and he has a very theatrical aversion to what he calls ‘woke’ politics,” she said.

The term “woke” means being attuned to social issues, particularly racial inequality.

On its own, ESG is more about data than a type of investing, such as socially responsible investing, but that has not stopped ESG from being a target in the culture wars that have escalated since the Trump presidency.

“Becoming aware of the lives and circumstances of people around you – how can that be a bad thing?” Holloman said.

DeSantis has also targeted LGBTQ issues, including signing legislation last year widely known as Florida’s “Don’t say gay” law, which prevents teachers from discussing sexual or gender identity with students under fourth grade.

“It’s important to speak plainly about these issues – it’s shameful,” Holloman said. “It’s absolutely repugnant.”

Republicans who have taken firm stances on what they call “wokeness” are doing so in order to define the debate and their opposition, said Andrew Otis, partner at Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel. They see it as a way of moving people’s opinions, Otis said.

“Ron DeSantis has made no secret of his anti-woke agenda. He’s running on it. If he were elected, I think he would bring his anti-woke policies from Florida to Washington,” he said.

It isn’t clear if anti-ESG stances alone have much support from voters, but those stances haven’t appeared to hinder US politicians.

“DeSantis won by a healthy margin and promoted the anti-woke agenda, and spoke about it in his acceptance speech,” Otis said. “Until that time at which the anti-woke agenda doesn’t result in winning elections, they’re going to use it.”

One tactic Florida appears to be considering is applying the state’s unfair, deceptive and abusive statutes to investigate financial institutions that consider ESG factors in investments, Holloman said.

Legislation on the horizon

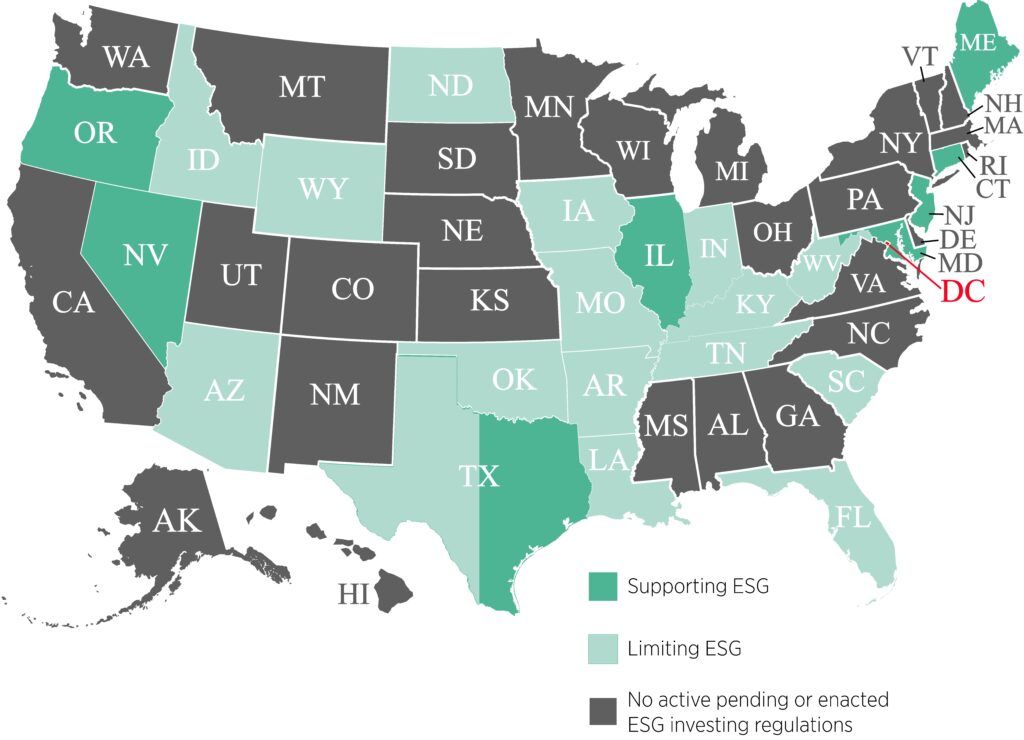

Map includes proposed or enacted state-specific regulation and does not address non-binding statements or pension-plan investment policy stances

To date, 16 states have proposed or enacted legislation that would tamp down on the use of ESG factors in investing public assets, according to data aggregated by law firm Morgan Lewis. Exactly half as many have done so for pro-ESG measures, that firm found.

“This is a hot political topic,” said Lance Dial, partner at Morgan Lewis. “The concerns that certain state legislatures have on ESG and allocating state resources remain … There is a perception that it is good politics.”

A relatively new tactic that has appeared in some pre-filed legislation would prohibit discrimination against companies based on their ESG scores from third parties, Dial noted.

“This is not going away. I don’t think it’s going to end with a whimper,” he said. “We’ll see more of these (laws) up to a point where it creates a federal issue.”

In that case, a federal court would likely decide where the boundaries are on the use of ESG in managing public assets.

It’s also worth noting that the US financial regulator the Securities and Exchange Commission is expected to soon issue a set of final rules on ESG that pertain to public companies, financial advisers and asset managers. The US Department of Labor also recently issued the final version of a rule on the use of ESG considerations in retirement plans and in proxy voting by pensions.

“Were there to be a change in [presidential] administrations, we can’t predict where any of this would rank in the various priorities they have,” Dial said.

There would be uncertainty around the DOL rule, but there is also little practical incentive for attacking it given that the final version took a “middle-of-the-road approach that is not prescriptive” in using ESG, he noted.

“From a legal perspective, it’s a solid rule.”

However, that rule could still be a political target in light of the recent focus against all things ESG.

In the current US Congress, there will likely be hearings around “wokeism,” including what ESG opponents say are restrictions on investing freedom, Otis said. That could tee up legislation that in the coming years could see more success, particularly with a change in administrations.

“You might see legislation in the House, and it could well pass the House, but obviously it won’t pass the Senate and would likely be vetoed by the president,” he said.

Investment provider worries

Clients who manage state assets have initially wanted to know how to navigate anti-ESG laws that have been enacted, such as the one in Texas against boycotting fossil fuel companies.

“Many of our clients are following this very closely to ensure they are able to discuss their ESG programmes in the right way, so they are not interpreted to be doing activities that are prohibited,” Dial said.

That does not mean that asset managers have to avoid ESG considerations at all costs. Even Texas’ law has a carve out allowing fossil fuel investment exclusions if done for ordinary business purposes, Dial said. That means that investment providers must describe ESG practices as being financially motivated, unless firms use ESG primarily for ethical or responsible reasons.

“People don’t want to be prohibited from considering ESG factors when it’s appropriate for their clients,” he said.

“If you have a financial ESG programme, you should describe it in those terms,” he said. “If you are an ethical ESG manager, you should clearly state so.”

Firms should also be careful to not overstate their use of ESG, to avoid greenwashing and attracting attention on that topic from the SEC, he said.

Nonetheless, asset managers are feeling pressure simultaneously from states – whether pro- or anti-ESG – and limited partners at the firms that are pressing for ESG strategies, Otis said. Satisfying all groups, especially for firms with business in Europe, where standards are higher, will be challenging, he noted.

“They’re going to have to assess their risk and then develop a strategy – but it’s going to take some thought,” he said. “Otherwise, they risk the possibility of being surprised with a sanction from a state or complaints that they are not following the ESG protocols that the limited partners are looking for.”

Oil investors still targeted

As some financial institutions have found, you can be a massive investor in the fossil fuels business and still be labeled a boycotter of that industry. Such has been BlackRock’s experience with anti-ESG policies in Texas.

Last year, West Virginia Treasurer Riley Moore barred several companies from doing business with the state, as they allegedly have sought to avoid investing in the coal industry. Those firms included Goldman Sachs, BlackRock, JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley, US Bancorp and Wells Fargo.

Some of the banks losing business with West Virginia have only a small percentage of lending associated with renewable energy, according to a report this week from Sierra Club, Fair Finance International, BankTrack and Rainforest Action Network. JP Morgan, for example, has just 2% of its energy-related lending in renewables, with the other 98% being in fossil-fuel activities, that report found. That figure was 3% for Goldman Sachs and 0% for Wells Fargo, according to the groups.

In Texas, there have been financial consequences as the biggest banks left the market. Research from the Wharton School found that the state’s issuers will pay an estimated $300m to $500m more in interest because of the drop in competition among banks on $31.8bn the state borrowed in the eight months after the state law was enacted.

Currently, five states have had pre-filed legislation on ESG issues, with only one bill being pro-ESG, Morgan Lewis’ data show. That could lead to more restrictions on financial services companies.

“They’re cutting people off at the states to financial resources over this issue,” Holloman said. “There is a lot to watch here.”